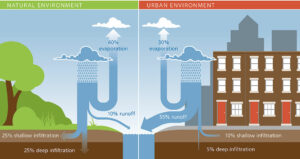

Stormwater runoff from our homes, businesses, and roads poses a threat not only to the quality of our local water resources but also to the safety of our communities from damaging flash floods. For these reasons, PRC and our partners have supported and funded the development of several watershed protection initiatives in southeastern Pennsylvania.

PRC’s watershed protection programs aim to address stormwater runoff through education, conservation, and the installation of green stormwater infrastructure (GSI). Under the umbrella of the Growing Greener Communities Initiative, these programs have engaged community members, municipal officials, and regional stakeholders to take action to improve water quality. One of these programs is Streamsmart Stormwater House Calls, started in 2017 to help property owners learn how to private homeowners better manage stormwater on their properties. with various GSI practices.

PRC and partners also conduct education and outreach campaigns centered around stormwater management through community workshops. The workshops focus on basic knowledge of stormwater and nonpoint source pollution and detail simple steps property owners can take to reduce pollution from their properties. Workshop participants also learn about the benefits of a rain gardens and other Green Stormwater Infrastructure on their property.

In addition, PRC also helps to support two distinct community municipal rain-garden programs: Hav-a-Rain Garden in Haverford Township (2014) and Upper Darby Rain Gardens (2020). These programs work with both private landowners and municipalities to install rain gardens. In addition to helping with installation and assessment, PRC also supports them through funding, grant writing, and administrative tasks.